I am an extremely quiet person, and since quiet constitutions are often regarded with suspicion, I appreciate films with extremely quiet heroes.

The quiet is what I admired most about Drive, at first. There is restraint in dialogue, and stillness in composition. Even Ryan Gosling’s facial features, unusually petite, restrain themselves from reaching a size better fitting the large plane of his face (it takes one big face to know another).

And out of Gosling’s very little mouth comes a very little voice, that says… very little. This muted calm, despite bursts of gory violence, is Drive’s greatest strength. Director Nicolas Winding Refn creates a persistant monotone mood consistent with lifetime long depression or certain drugs, and in this sleepy way it felt very similar to Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void. But in its characters’ outward emotional restraint and languid physicality it also reminded me of Bresson. This isn’t too surprising as American Gigolo’s influence is clear from the beginning:

and Paul Schrader is a great Bresson admirer, Gigolo being a remake of sorts of Bresson’s Pickpocket, which also shares interesting similarities with Drive:

“The style of this film is not that of a thriller. Using image and sound the filmmaker strives to express the nightmare of a young man who’s weaknesses lead him to commit acts of theft for which nothing destined him. However, this adventure and the strange path it takes, brings together two souls that may otherwise never have met.â€

But Drive doesn’t approach either of these films unfortunately, nor would I liken it to Taxi Driver, the other movie frequently referenced in discussion of the film. If we must compare it to an eighties movie, and Drive insists that we do, I find it to be most similar to Adrian Lyne’s Nine and a Half Weeks. Not in terms of story, though Mickey Rourke too is a sexy, small voiced, mystery man, but rather in unrealized potential: They are both visually satisfying films whose quiet characters suggest complexity but are in fact emotionally simple. The first twenty minutes of both films provoke an excitement that each following second slowly dampens.

An exercise in restraint and the creation of an unusual aesthetic is interesting, but our curiosity goes a short distance if there is no humor, emotional complexity or at least an interesting intellectual idea posited behind it. For example, Drive’s soundtrack enhances its style perfectly. It is echo-y, electronic, and eighties influenced, but there are many moments when the music dilutes the power of the scene.

When Irene (Cary Mulligan) and Gosling suddenly realize their affection for each other, music plays over alternating shots of Irene at her husband’s coming home party, and Gosling paused in work, alone in his empty apartment.

The music heightens the style, but in doing so simplifies the emotion, believing that this one dimensionality is somehow powerful or refreshing in its over simplification. It is not.

When a mainstream film appears to have formal ideas, or takes steps towards something different, it’s extremely exciting. It arouses. But so welcomed is this rare exhilaration that we risk being blind to the film’s secret mediocrity. Drive is interesting. At times it is good, even very good, but unfortunately never great, a fact mourned by all those who have qualms with the film, for it seems no one takes joy in pointing out Drive’s faults.

Despite my criticism, the urge to champion the film remains, and I’m afraid this review is conflicted, for though Drive’s aesthetic is what I criticize, it is also the reason I support it.

There aren’t boatloads of Hollywood action movies with such wide releases that give the same priority to visuals in this particular way. In mainstream cinema, great characters, though also rare, are more easily found than truly dynamic images or attention payed to a precise, cohesive style. It’s important that audiences who might not have interest in, or access to, smaller movies (the audience that probably saw Drive the first weekend), have the chance to see what can be done in a film, not just in an “artsy” film that’s already been compartmentalized as inaccessible, but one full of Hollywood stars. Though Drive is not a great film, it may be a stepping stone. Dare I say, Drive is the gateway drug of movies.

Everyone involved in film in one way or another can recall the one that stirred them to action. Even if you knew everything from Philco Playhouse to Dreyer’s mother’s boyfriend’s short films, chances are it was a contemporary movie that really sparked you to do more than watch, for nothing tops the energy of newness, the realization that the creation of art is not all in the past. Thanks to my parents, I was lucky enough to be surrounded by great movies, still, it was the semi-unspectacular American Beauty that cinched the deal. This shot in particular:

I was suddenly aware of the lighting. And the shot composition. And the music. It was different. After years and years of watching greater films, it was this one that began it all. I decided I would make movies one way or another.

Soon after seeing American Beauty, I had a doctor’s appointment. As she prepared an EKG I had insisted on for imaginary heart palpitations, the nurse asked me what I wanted to do. At that time I wanted to be a DP.

Nurse: So what do you want to do?

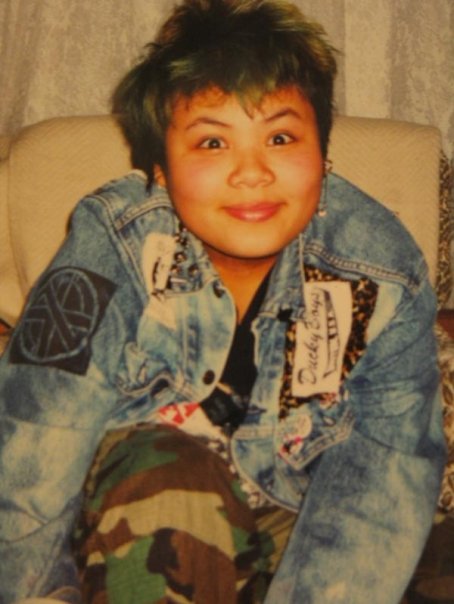

Fourteen year old me (see above): Cinematography

Nurse: Oh! What made you decide that?

Me (trying to give shortest possible answer): Uh, some movies look better than others…

Nurse: Really? That’s so smart! (to another nurse) Did you hear that? She said she realized that some movies look better than others!

I wasn’t sure if she was making fun of me or not (no kidding genius some movies look better than others), and I still don’t know, but I think that sums it up. Some movies look better than others and those movies, though unable to move us in greater ways, still play an important role. They are simple and accessible with enough hints at an artistic sensibility to energize… for a moment.

I think Drive will most satisfy teenagers who are discovering and experimenting with the power of aesthetic and style, but who, as they grow older, will abandon it for films revealing greater truths.

Comments

12 responses to “Drive”