I’m off to focus on my own films now.

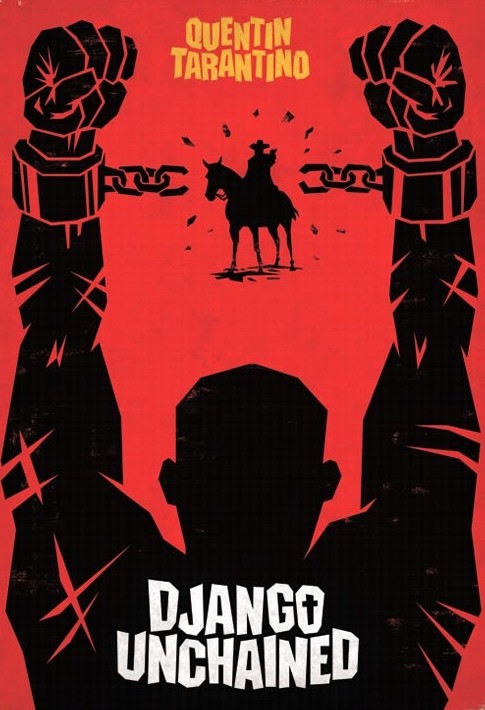

Here is my last post, my thoughts on Django, completely unedited. This is what something I write looks like before it’s anywhere close to being finished. Before I’ve toned it wayyy down or toned it way up, all out of order etc. I better get out of here before I start making disclaimers up the wazoo.

Blood is so red. Thank god for its color. Thank god for blood’s redness and thank god for red blood in Django. In January. Its good to see guts in the wastelands of winter.

In winter, the exteriors of everything rub on the exteriors of everything else. Coats pass other coats. Gloves shake other gloves, and the sole of every shoe treads on the outmost layer of a sleeping frog’s bunker.

I’ve never before understood the beauty of violence in a film the way I have when watching Django in January next to a brittle Christmas tree. Django was guts, the insides. and pointed out how we’ve been skulking around the outsides of slavery.

In movies about race especially, the form of the film is now more important to me than the content. If a film comments on race but is traditional in terms of narrative structure, casting, aesthetics etc in one way it’s defeated its points already. Fighting inequality is about changing a way of thinking. It involves locating the systems, large and small, that support tradition, and smashing them. A movie’s worth is directly related to how effectively it disrupts ways of thinking. The less power you have in the world, the more necessary this disruption is for your identity.

I’ve never been called a nigger and I keep this in mind when writing in favor of Django. Though I’m half black most people looking at me see my Malaysian side, and so don’t immediately recognize me as a negress, or even, as an angry but eagle eyed commenter once put it, a “tragic mulattaâ€. But though my ancestors were Virginian slaves, my experience with racism is different than a dark-skinned friend of mine who walked out on the film. This might seem like a strange distinction but it’s important to know whose immediate external character is on the line (how the outside world sees you immediately regardless of if its right or wrong). It’s certainly not the director’s.

Everything’s worth (friends, food, art, clothing) can be evaluated by whether it helps dismantle a constructed character or does it it coddle us into believing the process doesn’t exist or has been heroically, and most beautifully solved and soared beyond.

Hollywood allows black stories only in certain contexts. These are mainly historical dramas, comedies, or inspirational feel-good ___. Blacks are allowed to exist in our imagination in the appropriate places. This makes all these movies frustrating.

It’s frustrating that Django was made by a white director, someone who can play with black images at no risk to his own identity. White people telling black stories with black bodies is aggravating, unfair, infuriating, tiring, boring, and every other adjective. All are true. But maybe it takes Tarantino’s pulp aesthetic to revive slavery from the ‘ghost we handle with kid gloves’ way Glory, Lincoln, made us familiar with, to a real live thing that will be regarded as matter-of-fact.

It was a matter of fact reality for 400 years. Its that frankness that makes white audiences uneasy and causes black viewers pain. It is painful to remember that this brutality was a real every day occurrence. And that the threat of this violence was present every second of every day. Kerry Washington’s tiny perpetually rigid and tense frame communicated this so effectively, I cried nearly every time she appeared on screen. In Django no soaring music or somber negro spiritual plays while a slave is whipped or torn apart by dogs. We don’t have that magic carpet of emotional manipulation to come sweep us off our feet to hold us hovering at a safe distance from the horror. “Hush†the magic carpet usually says, “Yes, Denzel is being whipped, but he sheds a single tear in a way that’s dramatized just enough to allow you to feel deep sadness but not be overly traumatized. Hear the lone oboe play. Close..but not too close… now up up and awayyy!â€

That famous scene from Glory was an extremely sad one to watch. If something is ancient history, long gone, and is presented in a way that respects its place in history (with all your traditional period piece trappings) we can feel sad safely and we can mourn safely. Time grants us that buffer. We feel “sad for†the slaves and maybe we feel “sad for†our country. We’re more than familiar with experiencing sadness when watching films about slavery, but in this context, Slavery Sadness keeps the viewer at a distance. Slavery Sadness, has always allowed us hold ourselves at bay from the subject, perhaps because it’s too horrifying a truth to face. If we are feeling “sad for†something that means we are not right there with them. Not only are we somewhere else, perhaps on the other side of the room, but we are viewing them through time, sadness is slower to manifest in the individual after receiving violence, and our sadness is informed by history. Ferris Bueller feels sad watching Denzel, we feel sad watching Denzel, but Denzel himself feels fear, number one, then pain, humiliation, and anger. Sadness is too small an emotion. Despair, grief, numbness.

But if slavery is suddenly wrenched from the holy bosom of history that Lincoln, Glory, Amistad, etc cling to, and the appropriate historical trappings and negro spirituals are discarded with, replaced instead with blaxploitation camera work, dialogue with the cadence of modern speech, and contemporary music, it instantly becomes more immediate and we’re faced with other unexpected emotions. In a flashback scene where Django and Brumhilda are captured attempting to escape, an Anthony Hamilton/Elayna Boynton song plays. With the sound of barking dogs behind then, Brumhilda’s face trembles with terror. She kisses Django hard on the mouth and they run on. Captured, Django pleads unsuccessfully for his wife to be spared the whip. She is strung up by each hand and as the whip meets her back her mouth contorts. She screams in pain and fear. When watching this scene, I felt not only Brumhilda’s terror, but in that hard kiss, the pain and helplessness of being parted with the one you love, and the inability to protect them. There has never been a depiction of slavery that has made me feel so immediately connected to the emotions of the individual slave herself, not of my emotions about “slaveryâ€, as an institution.

The gruesome Mandingo fight scene may have been historically inaccurate, but it depicted the despair, grief, control, and animalization of male slaves in a way I haven’t previously seen on screen. If historical revisionism in a film about slavery produces emotions more truthful to the actual experience of slavery (fear, disgust and anger not sadness), then it succeeds in leading us closer to the truth of our history and to ourselves. (every historical film compresses and combines ideas, emotions, and conversations in order to convey them in a 2 hour film)

When a person from the group in power employs historical revisionism to tell a story about the group with lesser power, it should always be regarded with suspicion. America has difficulty in understanding the facts of it’s own crimes. Many people fight everyday for their experiences to be respected as legitimate. The most destructive effects of racism is not the blatant, but each generations inheritance of the micro effects of dehumanization. I think there is fear that a tale where a slave rides off into the sunset after blowing up white people, will allow white viewers to happily trot off with him savoring a history that assuages their guilt by applauding their aggressive liberalism.

There is concern, a legitimate concern, that White Americans will take any opportunity to look away. And if they look away, we continue to be invisible.

I’m sure that Django is an effective escape route for many white viewers, but I’m okay with letting them go because I suspect that for many others, the film re-introduces something they’ve intellectually long understood as “tragicâ€, to produce a truer more immediate emotional understanding of it.